Future Car Sets for Electrifying Success

[29 April 2018, The STAR]

The automotive industry is looking ahead to when academic excellence and corporate expertise 'combust' to disrupt the energy industry.

WITH charging stations more common, electric cars are touted as the way forward in the not-too-distant future. Last July, Volvo announced that it is phasing out cars that rely on combustion engines. Every new model launched from 2019 will have an electric motor – a first by a premium carmaker that has always been at the forefront in applying new technology to the carbon-fuel-charged internal combustion engine.

The trend of electric-powered cars is growing far beyond hybrids as the shift away from the 200-year-old internal combustion engine technology gathers pace. France and Britain, for instance, plan to ban the sale of new petroleum-burning vehicles by 2040.

Even so, gas and diesel powered engines are not dead yet.

Mazda recently announced a big advance in a combustion method that could result in gasoline engines becoming 20-30% more efficient than its current best engines. To be introduced in 2019, in this method gasoline is ignited without using spark plugs.

Experts contend that improvements in internal combustion engines will continue. John Heywood, an MIT mechanical engineering professor predicts that by 2050, 60% of light-duty vehicles will still have combustion engines.

Closer to home, for almost a decade a research team has been toiling over improvements on the free piston engine – attempting to produce an engine without a crankshaft, with floating pistons to capture the power of combustion with measured control. Traditionally, the crankshaft controls the piston while imposing limitations on combustion efficiency. Getting rid of the crankshaft means combustion control.

Its greatest advantage is its performance efficiency, compared with standard engines. Taking that concept further, with its first patents from around 1940, the Free-Piston Linear Generator (FPLG) is a free-piston engine with a linear alternator. It converts chemical energy from fuel straightaway into electrical energy.

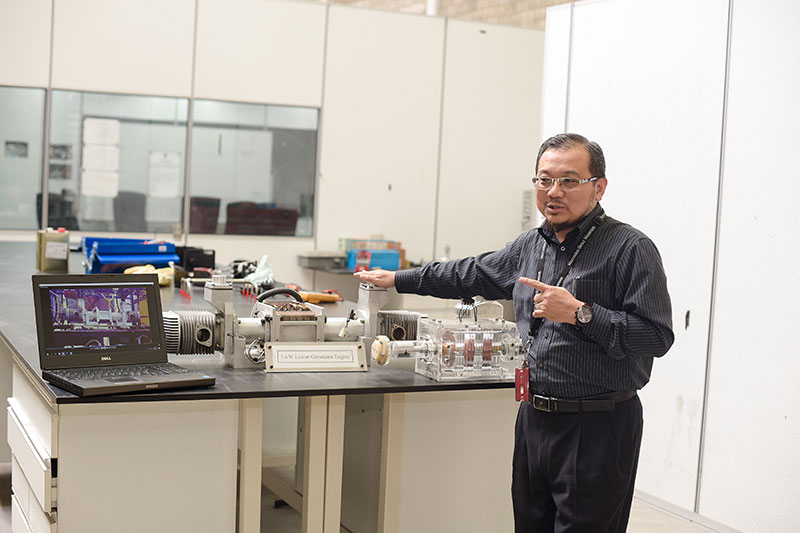

When Professor Abdul Rashid Abdul Aziz, Director of the Institute of Transport Infrastructure for Smart Mobility, and his team first embarked on this project, they thought it would take them three years to reach their target. They achieved their goal three prototypes and nine years later, in March 2017. The FPLG finally achieved its objective, managing to combust and producing electricity.

Despite the slow progress, the UTP team determinedly pressed on, undertaking advanced explorations into the possibilities of an alternative to conventional power generators such as micro turbines and diesel generators. The Free Piston Engine (FPE) was identified as an option, the key being piston motion control. This is the main challenge before the end result of the research can be commercialised.

Collaborating with industry

However, in developing this capability, Rashid realised the need for collaboration. "You cannot do everything yourself. That's the recipe for failure. We cannot be experts in all the necessary areas," he says.

Through their strong, long-term links with the University of Brighton, they chose to collaborate on a four-year project with UK company Libertine FPE, designer and manufacturer of linear generators and piston power systems. Both partners have equal equity in the FPLG development.

Building Libertine's Linear Power Systems technology into their research engine programme allowed UTP to accelerate its research into a high-efficiency, fuel-flexible combustion system.

Libertine FPE's CEO Sam Cockerill says the collaboration with UTP has greatly helped his company. His company has focused and advanced their technology in this space, providing a template for their relationship with other FPE developers. This benefits UTP, he feels, since together they are able to share technology platform developments across multiple FPE programmes. This enhances each one's cost-effectiveness and performance. To Cockerill, UTP is an interested and engaged partner with very clear research objectives.

It is crucial, Cockerill feels, for industry players and universities to collaborate. This is because the number of university FPE R&D programmes, especially for smaller engines, has rapidly risen in the last two decades.

Towards clean, green energy

Rashid was also the past Head of UTP's Centre for Automotive Research & Electric Mobility (CAREM). He explains that depending on the capacity, the engine model can be used for any application requiring electricity, including future electric vehicles and stationary power genset. "The size of the engine will shrink to about one-fourth of the current size and its weight reduce as much, if not more."

The engine is also produced at lower cost due to fewer mechanical components. "To realise a software-controlled engine without any mechanical constraints – that's where the opportunity exists for combustion optimisation," adds Cockerill.

So far, such generators are not available in the market, but many companies around the world are working on similar concepts. Rashid and Cockerill agree that when the FPLG is successfully delivered, it could disrupt the energy industry. It is the future, they think, for generating clean and green energy.

Without conventional constraints on motion, the generator operates at a higher thermal efficiency than in conventional engines and can run on different fuel types. That includes natural gas as an option and a higher thermal efficiency than in conventional engines. "With less volume, weight and size, you're able to generate the same amount of power," says Rashid, "while reducing costs of production, operations and maintenance. You'll need to see it to believe it."

The UTP team have completed all the design and machining of their latest prototype. They are now looking forward to running major tests with their collaborating partner by the end of this year. Rashid aims to commercialise the FPLG by 2019, mainly for use on offshore oil and gas platforms.

If an institution is serious about commercialisation, it is best to collaborate with those who are at the forefront of technology right from the beginning, asserts Rashid.

While he feels a university's strength is on the fundamentals of engineering, it can still benefit greatly in product development with input from a design engineering company's perspective.

"I realised many people are replicating the same work. We should instead collaborate and work together." While it is a challenge to work with various stakeholders – from investors to research students, Rashid appreciates the content sharing and knowledge exchange.

In his lab, research officers, MSc and PhD students, and technologists continuously run tests on the prototype, which looks deceptively simple. They study, photograph and collate data on the flow of air and spray, using state-of-the-art laser measuring systems. "Research is always 50-50 with an equal chance of success or failure. You'll never know the result until the end."

Research life

Ezrann Zharif Zainal Abidin

Research Scientist and Manager, Smart Mobility Division

EZRANN Zharif Zainal Abidin was a Master's student when he first started work on the Free Piston Linear Generator project. "My baby," he proudly claims, having waited nine years for it to show its first result.

With a lot of discussion and exchange of ideas, Ezrann finds his work gratifying. "Prof Rashid allows a lot of freedom for us to think and to execute our ideas. I really like his style of leading this Centre in implementing new methods." What he finds most interesting and challenging is, when faced with new problems, they are allowed to argue and innovate, with positive feedback that allows them to overcome challenges.

Being a researcher requires a lot of patience and perseverance. "It's continuous. You don't give up on what you believe." Helping to generate energy responsibly is what drives him, "with lower emissions to help save the environment." That is why he persisted, even when the results took almost a decade to achieve.

UTP's hallmark of high standards and excellence is what drives all its research. Research is not about business or money. "It's in the value of trying to help mankind and the planet. The reward for me is if you can create something novel that helps nature and the environment…then that's the value I helped create for people."